Economic Rationalizations For Compulsory Unionism Are Just as Weak as the Others

JURIST – Forum: ‘Right to Work’ in Michigan: Depleting Unions …

A recent commentary by Michigan law professor Susan Bitensky relies heavily on economic data to justify monopolistic unionism, but totally ignores the undeniable fact that average job and income growth are far more rapid in Right to Work states than they are in forced-unionism states.

This blog post follows up on the February 3 discussion here of an anti-Right to Work commentary by Michigan law professor Susan Bitensky, published by The Jurist a few weeks ago (see the link above).

Previously, I explained why Bitensky’s assumption that all union nonmembers subject to monopoly union representation in the workplace thereby enjoy economic “benefits” is simply false.

Today I focus on Bitensky’s claim that “where [Right to Work] statutes exist, working people across the enacting state suffer serious adverse economic consequences . . . .”

It is striking that, although Bitensky takes up two long paragraphs citing data purportedly documenting this claim, she fails to cite a single statistic showing that forced-unionism states enjoy more rapid growth in any type of employee compensation, cash or noncash, than Right to Work states. In Bitensky’s defense, such statistics are extraordinarily hard to find.

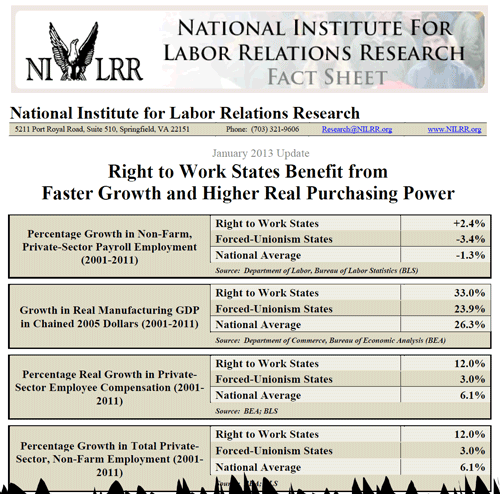

The fact is, inflation-adjusted U.S. Commerce Department data actually show that, from 2001-2011, the dollar value of compensation furnished by private employers to employees in Right to Work states (not counting Indiana and Michigan, which did not adopt their Right to Work laws until 2012) increased by 12.0%. That’s nearly double the national average of 6.1%, and quadruple the forced-unionism state average of 3.0%. And the Right to Work advantage is not due to a few outliers. Ten of the top 14 states for private-sector compensation growth over the decade are Right to Work states. But 17 of the 18 states with the lowest compensation growth (including all four states with negative growth) are forced-unionism states.

More rapid growth in private employer expenditures on wages, salaries, benefits and bonuses goes hand in hand, not surprisingly, with far superior growth in the number of people covered by private health insurance. From 2001 to 2011, despite the enormous setback of the Great Recession, Right to Work states as a group (again excluding Indiana and Michigan) added roughly 870,000 people, net, to the ranks of the privately insured, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. Meanwhile, forced-unionism states saw their ranks of privately insured people shrink by 7.71 million.

In avoiding completely data related to economic growth, Bitensky also fails to appreciate the huge impact of net domestic migration on the statistics she does cite. Many forced-unionism states have persistent and substantial net domestic out-migration. States with net out-migration often experience far greater net losses of adults with less than a college education than of adults with a bachelor’s degree or more.

Moreover, states with net out-migration are typically losing far more young adults, regardless of educational attainment, to other states than they are people in other age brackets, because young adults who don’t yet have children are more apt to move from state to state than virtually any other demographic group. Take pre-Right to Work Michigan, for example. For 2000 to 2011, even as the U.S. population, aged 25-34, increased by 4.7%, the Wolverine State’s population in that age bracket fell by 14.1%.

Since young adults are less apt to have health insurance in addition to being more apt to move from state to state, Michigan’s extraordinary and ongoing losses of young adults has had a side effect of raising the state’s health-insurance coverage rate over time. And this phenomenon has been apparent not only in Michigan but in a number of other forced-unionism states for decades.

Obviously, a state that raises its overall health-insurance coverage through massive net out-migration of its young-adult population has nothing to boast about when it comes to access to insurance. For that reason, the comparative data Bitensky cites on insurance coverage are basically useless. Growth or decline over time in the number of people in a state covered by private health insurance is a far better gauge of success than the percentage of residents covered at any particular time. And by the growth standard forced-unionism states have been faring poorly relative to Right to Work states for many years.

Failure to take into account economic growth is hardly the only problem with Bitensky’s effort to build an economic case for compulsory unionism. I will discuss some of the other problems with her argument in a post next week.