Employees Should Have as Much Freedom as Business Owners

A well-written article by Steve Horwitz appearing in the June issue of The Freeman (see the link above) recounts the story of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Schechter decision of 1935. Schechter, a seminal case that is insufficiently well known outside the legal profession, concerned four Hungarian-born brothers and businessmen in New York City. The Schechters were kosher butchers. As Horwitz explains, the brothers were “poultry middlemen, buying chickens from across the country, then butchering and selling them to the New York City market, mostly to retailers who then sold them directly to consumers.â€

Their trouble started after Congress adopted, and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed into law, the so-called “National Industrial Recovery Act†(NIRA) of 1933. The NIRA was based on the now-discredited theory that the Great Depression then underway had been caused by “cut-throat competition†among employers as well as employees. It authorized business associations and a new federal bureaucracy overseeing them, the National Recovery Administration (NRA), to write legally binding codes for participants in their industry. The NRA’s codes often prohibited individual businesses from setting their prices “too low†and from furnishing customer service that was “too good.â€

The main problem of the Schechters was Section 2, Article 7 of the NRA’s “Code of Fair Competition for the Live Poultry Industry of the Metropolitan Area in and about the City of New York.†Though, as Horwitz notes, this “sounds like something out of Atlas Shrugged,†it was all too real. Section 2, Article 7 mandated “‘straight killing,’ which meant that customers could not select specific birds out of a coop. Instead, they had to select a coop or half coop entirely.â€

Following their understanding of kosher law, the Schechters had always allowed customers to choose the particular birds they bought. In other words, the Schechter’s customers, exercising their own judgment about whether each chicken was healthy and worth buying, had the prerogative to purchase some or most, but not all, of the chickens in a coop or half coop. The brothers did not think they should have to cease offering customers this valued service merely because their business competitors, with the help of NRA bureaucrats, were ordering them to. They took their case all the way to the Supreme Court, and in late May 1935 the nine justices ruled unanimously in the brothers’ favor.

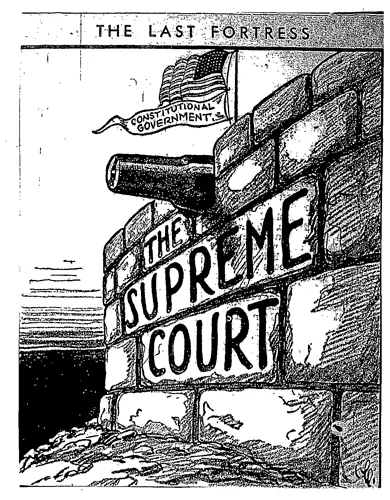

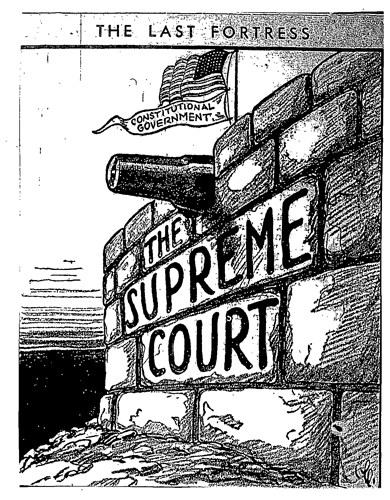

The Schechter decision was an important landmark for business owners’ constitutional freedom to serve their customers to the best of their ability even if misguided and self-serving politicians regard such competition as “cut-throat.†Unfortunately, neither the federal court system nor Congress has ever recognized that employees have an analogous freedom under the Constitution to provide superior service to their employer. Under the National Labor Relations Act, union officials wielding monopoly-bargaining power can still today get individual employees punished for violating industrial “codes,†that is, evading union work rules that prevent them from doing their jobs as efficiently and well as possible.

Whether they are union-free or unionized, individual employees should have just as much freedom under the law to do the best job they can for their employer as employers have to provide the best service for their customers. It’s time to “schechterize†labor relations in the American workplace.