Federally-Imposed Forced Union Dues Are Unconstitutional

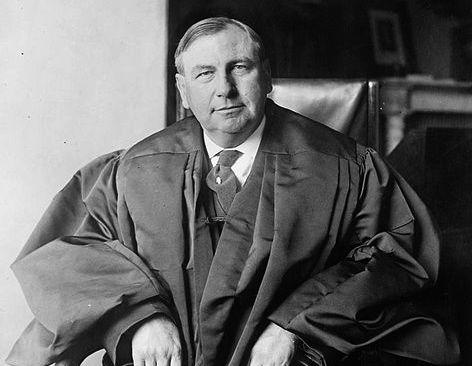

Writing for a unanimous High Court in 1944, Chief Justice Harlan Stone declared that, whenever union bosses obtain monopoly power to speak for all employees in a “bargaining unit” under the auspices of government policy, that power must be “subject to constitutional limitations….” Image: National Photo Company/Library of Congress

More than 70 years ago, when Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad came before the U.S. Supreme Court, there was no federal law prohibiting race-based job discrimination perpetrated by employers or other private parties.

As a consequence, the railroad executives who were the principal defendants in this case were able to contend that a racially discriminatory deal they had cut with union bosses, ultimately resulting in job losses for three-quarters of the African American firemen who had been employed by the railroad, was, as the Alabama Supreme Court had already held, a “lawful contract entered into in a lawful manner.”

However, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously disagreed, largely because the firemen’s union bosses who had demanded favoritism for white job seekers were not ordinary private citizens.  The reason: Under Section 2, Fourth of the Railway Labor Act (RLA), these union officials were the “exclusive” (monopoly) bargaining agents of every firemen employed by the railroad company.

In the words of Dr. Charles Baird, a professor emeritus of California State University, East Bay, and an internationally recognized expert on labor policy, RLA Section 2, Fourth, and analogous provisions in other federal statutes and in many state laws stipulate that a “union that receives a majority of votes in a certification or representation election becomes the ‘exclusive bargaining agent’ for all the worker who were eligible to vote in the election.”

Under laws like the RLA, Baird wrote:

A union . . . represents all the workers who voted for it, all the workers who voted against it, and all the workers who did not vote. It is a winner-take-all . . . system patterned after the rules for electing members of Congress. Where there is a certified union, individual employees are prohibited from representing themselves in matters having to do with wages and salaries and other terms and conditions of employment (the matters that come under “the scope of collective bargaining”).

It is important to recognize that under the principle of exclusive representation, created by federal statute, the minority (all workers who do not vote in favor of the winning union) are put to a choice between submitting to the will of the majority regarding the sale of their individual services or losing their jobs. That is governmentally imposed coercion, pure and simple. The fact that workers can opt out of the unwanted representation services of a certified union by quitting their jobs does not mitigate the coercion. If an individual owns his own labor, and has a further right to enter into contracts with any willing buyer of that labor on terms that are mutually acceptable, then exclusive representation overrides those rights. Such an arrangement sacrifices individual rights to group rights . . . . And since exclusive representation exists solely by virtue of federal statute, the federal government, not any private party, is the source of the coercion.

Acknowledging that the federal government was indeed the source of the coercive power wielded by firemen’s union bosses, Justice Harlan Stone concluded in his opinion in Steele that, if the RLA actually permitted the forging of racially discriminatory contracts such as the one being challenged, it would violate the Fifth Amendment rights of the employees who lost their jobs. Under the RLA, Stone explained, a union “is clothed with power not unlike that of a legislature which is subject to constitutional limitations on its power . . . .”

The Steele court allowed the RLA to stand only by concluding, somewhat creatively, that the law tacitly prohibited railroad union bosses from using their “government-granted monopoly power to drive African Americans from the labor force,” as George Mason University law professor David Bernstein has put it.

In his 2001 book, Only One Place of Redress, Bernstein went on to note that the High Court’s World War II-era reproof and warning to Big Labor to stop using its government-granted monopoly-bargaining privileges to foster job discrimination against blacks and other racial minorities mostly fell on deaf ears. But Steele at least established that, whenever union bosses are “cloaked with power” akin to that of legislators by a federal or state statute, Big Labor must be subject to constitutional constraints.

That means, for example, that union officials may not use their government-granted powers to trample the individual employee’s “freedom to engage in association for the advancement of beliefs and ideas.“ In his opinion for a unanimous High Court in the 1958Â NAACP v. Alabama case, Justice John Marshall Harlan insisted that such freedom is “an inseparable aspect of the ‘liberty’ assured by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which embraces freedom of speech.”

Harlan explained that it is “immaterial” whether the “beliefs sought to be advanced by the association pertain to political, economic, religious or cultural matters, and state action which may have the effect of curtailing the freedom to associate is subject to the strictest scrutiny.”

Since NAACP v. Alabama was handed down, federal courts have consistently interpreted this precedent as establishing that the individual has a constitutional right to join and support a union.

And once the federal court system recognized that the First and the Fourteenth Amendments prohibit laws curtailing the personal right to join a union or support a union, the inevitable logical conclusion to draw was that the personal right not to join or support a union must be equally protected under the law.

As early as 1966, then-U.S. Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen (R-Ill.) emphasized the need for consistency in federal labor policy in an article published in the DePaul Law Review:

[T]he right not to join a union is a necessary corollary of the right to join, for without a right not to join there can be no such thing as a right to join. Freedom rests on choice, and where choice is denied freedom is destroyed as well.

Very arguably, the federal imposition of union monopoly bargaining in Section 2, Fourth of the RLA and in Section 9(a) of the National Labor Relations Act is in itself a violation of the freedom of association of workers who choose not to be union members, since it forces them to allow an unwanted union to negotiate their pay, benefits, and terms of employment.

But even if government-promoted monopoly bargaining is not seen as directly violating the Constitution, there clearly is a violation when Big Labor wields this privilege to extract an agreement from an employer forcing independent-minded employees to join or pay dues or fees to a union as a job condition.

To paraphrase NAACP v. Alabama, it is “immaterial” whether the monopolistic union contract union officials were able to obtain because of state action forces nonmember employees to finance the propagation of “political, economic, religious or cultural” views with which they disagree. Regardless, it is an infringement of the employees’ First Amendment rights.

By late this spring or early this summer, the U.S. Supreme Court is expected to issue its decision in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, a case that challenges the constitutionality of forced union dues and fees when a government entity is the employer. In the wake of last month’s oral arguments, most court watchers are predicting that a narrow High Court majority will rule that such coercion is barred under the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

It goes without saying that when government officials are party to a forced-dues deal, the deal is a state action. But as we have just seen, private-sector forced union dues are also a state action, since it is government-imposed monopoly bargaining that empowers Big Labor to make them a condition of employment.

In all cases, government-promoted compulsory union dues are unconstitutional.