Is Judge Diane Wood Ignorant of Federal Labor Law, or Dishonest About It?

U.S. 7th Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Diane Wood obviously feels strongly that federal labor policy should empower union bosses in all 50 states to cut deals with employers forcing employees subject to “exclusive” union representation in the workplace to pay union fees, or be fired. Â However, judging by her long and angry dissent (see the link below, starting on page 32) from the majority opinion on a three-member 7th Circuit panel upholding Indiana’s Right to Work law this week, she has a very difficult time explaining why on rational grounds.

In his decision (available at the beginning of the link below), Judge John Daniel Tinder, joined by Judge Daniel Manion, ably exposes several of the fallacies in Wood’s dissent.

For example, as Tinder points out, Wood accepts without question the fact that, under longstanding U.S. case law, the provision in Section 8(a)(3) of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) permitting union officials and employers to make union “membership” a job requirement has been interpreted to mean that employees may under federal law be required either to join a union, or alternatively to remain nonmembers, but fork over forced fees for union bargaining activities. Â At the same time, she rejects out of hand the view, which has been accepted by federal courts for at least three decades, that the provision in NLRA Section 14(b) recognizing states’ prerogative to prohibit compulsory union “membership,” not withstanding the fact that Section 8(a)(3) sanctions it, should be interpreted to mean that states may prohibit not just forced union membership per se, but also all forced union dues and fees.

Tinder reminds Wood that, with rare exceptions, if the same word is used twice in a statute, courts are obliged to give the word the same meaning wherever it appears in the statute. Â She all the same appears determined to define “membership” broadly in NLRA Section 8(a)(3), but much more narrowly in Section 14(b), without offering any explanation why.

Other glaring errors in Wood’s dissent are not discussed in the majority opinion, but are also worthy of attention. Â One key failure is Wood’s mistaken assumption that state Right to Work laws were not permissible under the original NLRA of 1935, and only became so as a consequence of Section 14(b), included in the Taft-Hartley amendments of 1947.

In reality, the U.S. Supreme Court explicilty ruled in the Algoma Plywood decision of 1949 that state Right to Work laws were never preempted by the NLRA. Â As Justice Felix Frankfurter wrote for an 7-2 High Court majority, Â Section 8(3) of the original NLRA

merely disclaims a national policy hostile to the closed shop or other forms of union-security [i.e., forced-unionism] agreement. Â This is the obvious inference to be drawn from the choice of the words “nothing in this Act . . . or any other statute of the United States,” and it is confirmed by legislative history.

The inference to be drawn from this passage in Algoma Plywood is that the original NLRA did not preempt ANY state or territorial regulations or prohibitions of forced union dues and fees. Â If this is true of the original NLRA, it must be truer still of the NLRA as amended by Taft-Hartley. Â No wonder Wood’s dissent simply assumes Algoma Plywood out of existence!

Yet another gross error in Wood’s dissent not discussed by Tinder is her false assumption that federal labor law prohibits contracts in which union officials represent their members only, and authorizes only “exclusive” representation in which union members and nonmembers alike are subject to the job conditions negotiated by the union.

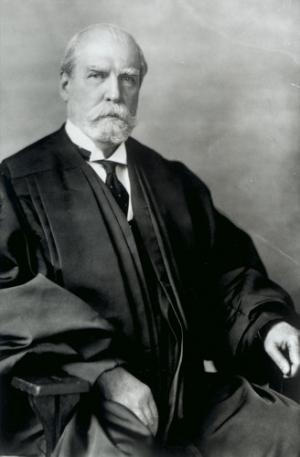

The reality is that, three quarters of a century ago, a High Court majority led by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes explicitly found in Consolidated Edison v. NLRB that, absent the existence of a monopoly-bargaining deal in a workplace, contracts designating a particular union as the bargaining agent only “for those employees who are its members” fall into the framework of protected activity under Section 7 of the NLRA and are certainly permissible. Â Subsequent High Court rulings have confirmed that Hughes’ 1938 decision in Consolidated Edison applies as well to the NLRA as amended by Taft-Hartley.

When she writes that state Right to Work laws prohibiting all forced union dues and fees would be constitutionally acceptable and compatible with federal labor policy “if unions were permitted to deny services to nonmembers,” is Wood really unaware that, unless they seek and obtain monopoly-bargaining privileges, union bosses are indeed permitted under current law to deny services to nonmembers? Â Or is she just being dishonest in an effort to encourage a future Supreme Court to overturn all state bans on forced dues and fees?

Three quarters of a century ago, a U.S. Supreme Court opinion by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes upheld the permissibility under federal labor law of contracts designating a union as the bargaining agent only “for those employees who are its members.” But a dissenting opinion by pro-forced unionism 7th Circuit Court of Appeals Chief Judge Diane Wood issued this week completely overlooks Hughes’ landmark decision in Consolidated Edison v. NLRB. Image: Wikimedia Commons