Michigan Union Bosses Would Have a Good Point — If Americans Weren’t Free to Move From State to State

Firefighters, Nurses and Working Families Ask State Senators to Avoid Divisive Politics

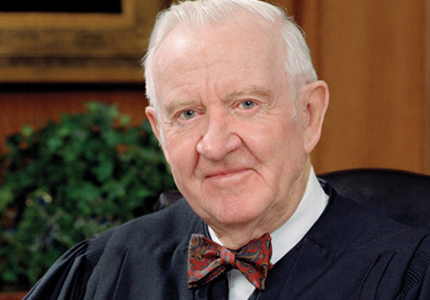

As U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens elucidated 13 years ago, the Constitution protects the right to enter one state and leave another, the right to be treated as a welcome visitor rather than a hostile stranger, and the right to be treated equally with native-born citizens. In trying to concoct a case against passage of a Michigan Right to Work law, union propagandists are ignoring these simple and obvious facts. Graphic: veracitystew.com

Since the early 19th Century, federal courts have recognized freedom of movement as a right protected by the U.S. Constitution. In Paul v. Virginia (1869), the High Court defined freedom of movement as “right of free ingress into other States, and egress from them.” In 1999’s Saenz v. Roe, Justice John Paul Stevens, writing for the majority, specified that the Constitution protects the right to enter one state and leave another, the right to be treated as a welcome visitor rather than a hostile stranger, and the right to be treated equally with native-born citizens.

The principle and practice of the freedom of movement have a powerful impact on a range of data commonly used to gauge states’ relative economic performance, such as unemployment rates, educational attainment, poverty, and, of special note for us today, health-insurance coverage rates.

Some states have persistent and substantial net in-migration from other states. Others have persistent and substantial net domestic out-migration. States with net out-migration often experience far greater net losses of adults with less than a college education than of adults with a bachelor’s degree or more.

Moreover, states with net out-migration are typically losing far more young adults, regardless of educational attainment, to other states than they are people in other age brackets, because young adults who don’t yet have children are more apt to move from state to state than virtually any other demographic group.

Take Michigan’s net out-migration, for example. From 2000 to 2011, even as the U.S. population, aged 25-34, increased by 4.7%, the Wolverine State’s population in that age bracket fell by 14.1%.

Since young adults are less apt to have health insurance coverage in addition to being more apt to move from state to state, Michigan’s extraordinary and ongoing losses of young adults has a side effect of raising the state’s health-insurance coverage rate over time.

Obviously, a state that raises its overall health-insurance coverage rate through massive net out-migration of its young-adult population has nothing to boast about when it comes to access to insurance. That’s why growth or decline over time in the number of people within the state covered by private health insurance is a better gauge of success than the percentage of residents covered at any particular time.

By the more meaningful standard, Michigan has an extraordinarily poor record. From 2001 to 2011, according to U.S. Census Bureau data, the number of Michiganians with private health-insurance coverage fell by 15.6%. Out of the 50 states, only Ohio’s 15.7% slide was steeper, and just slightly at that. (See the first link above for more information.)

In light of the relevant facts, it takes a lot of nerve (or, perhaps, plain ignorance) for top union officials in Lansing to oppose ongoing efforts to pass a Michigan Right to Work law on the grounds that such a law would somehow reduce health-insurance coverage across the state. Yet that is exactly what Big Labor bosses in Michigan are doing now. (See the second link above.)

The fact is, private health insurance coverage fell sharply nationwide during the Great Recession of 2007-2009 as millions of jobs providing this important benefit disappeared. However, private coverage has since enjoyed a robust recovery in the 22 states that had Right to Work laws on the books barring forced union membership, dues and fees as of 2011. (Indiana became the 23rd Right to Work state only this year.) Meanwhile, forced-unionism states as a group have experienced no recovery whatsoever.

From 2001 to 2011 (the last year for which data are available), despite the enormous setback of the Great Recession, Right to Work states (excluding Indiana) added roughly 870,000 people, net, to the ranks of the privately insured, whereas forced-unionism states saw their ranks of privately insured people shrink by 7.71 million.

Judging access to health insurance in any state by the current coverage rate alone, as Michigan union spokesmen are currently doing, would make sense if Americans weren’t free to move from state to state, or if they rarely took advantage of that freedom. But since Americans can and often do make interstate moves, Big Labor’s health-insurance “talking point” against a Michigan Right to Work law actually makes no sense at all.