The ‘Facile Generalization That There Is No Constitutionally Protected Right to Public Employment Is to Obscure the Issue’

In their November 6 merits brief in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association (accessible at the first link below), a team of government union lawyers led by David Frederick of the Inside-the-D.C. Beltway firm of Kellogg, Huber, Hansen, Todd, Evans & Figel make extraordinary explicit and implicit claims regarding how much power over individual educators state lawmakers may accord their clients without violating the U.S. Constitution.

In fact, the hierarchy of the CTA and its gargantuan parent union, the National Education Association (NEA), effectively contend, although without daring to say so bluntly, that talented and hard-working teachers who aren’t union members and get paid LESS as a consequence of being under a union monopoly can constitutionally be compelled by the government to fork over dues or fees to the union as a condition of employment. Â (See the November 9 Institute blog post accessible in the second link below for more information on how teacher union lawyers arrived at this position.)

In taking a minimalistic view of the constitutional rights teachers and other public employees enjoy vis-a-vis government union bosses and government employers, Frederick and his team rely heavily on a line of High Court precedents such as Pickering v. Bd. of Ed. (1968).

Under Pickering and other such cases, government employers may punish or even fire employees for publicly expressing their opinions on employment-related matters if such restrictions arguably promote “the efficiency of public services . . . .”

What the Frederichs respondents apparently have forgotten is that federal courts have already repeatedly ruled that the government as an employer does not have such wide “constitutional latitude” to limit the First Amendment freedom of public employees to join a labor union.

In 1969, a federal court overturned North Carolina’s statutory provisions restricting municipal employees’ right to join and assist labor organizations, finding them to be “an abridgment of the freedom of association as protected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.”

A month before this decision (Atkins v. City of Charlotte) was issued, the Eighth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals similarly ruled in American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees v. Woodward that Nebraska public officials had violated the Constitution when they fired two employees for joining a union.

In support of its decision, the Eighth Circuit opinion quoted this passage from the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1952 ruling in Wieman v. Updegraff:

[T]he facile generalization that there is no constitutionally protected right to public employment is to obscure the issue. . . . We need not pause to consider whether an abstract right to public employment exists. It is sufficent to say that constitutional protection does extend to the public servant whose exclusion . . . is patently arbitrary or discriminatory.

The decisions reached by the district court in Atkins and the appellate court in Woddward quickly gained wide acceptance in federal courts across the country.

Of course, other established court precedents make it clear that, if a public employee’s choice to associate with a labor union is constitutionally protected, his or her choice not to associate must be similarly protected. As the High Court declared 72 years ago in W. Va. Bd. of Ed. v. Barnette, the government has no legitimate authority to “prescribe what shall be orthodox” in the realm of politics, conscience, and ideas.

Consequently, since government restrictions on the individual public employee’s freedom to join a union have been regarded as unconstitutional (except in rare instances where national security is potentially at stake) for nearly half a century, restrictions on the freedom not to join or bankroll a union must also be unconstitutional.

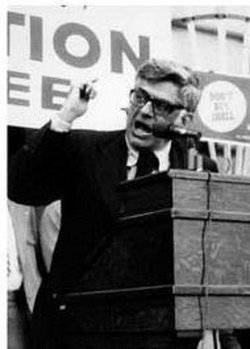

Back in 1969, government union chief Jerry Wurf and his team of lawyers, acting on behalf of a pair of their rank-and-file activists in Nebraska, persuaded a U.S. federal appeals court that state policies prohibiting union membership as a condition of employment violate the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. But today the Big Labor lawyers representing California teacher union officials before the U.S. Supreme Court in Friedrichs are singing an altogether different tune. Image: findagrave.com