Union Violence, Then and Now

“The Right to Work”, by Ray Stannard Baker, McClure’s Magazine …

Limitations on violence under law tested anew … – The Buffalo News

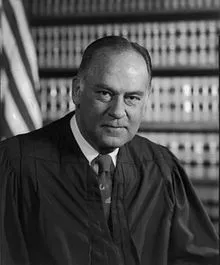

Justice Potter Stewart

Last week a Bloomberg commentary by Elizabeth Tandy Shermer, a history professor at Loyola University Chicago, steered curious readers to a gripping piece of journalism that is over a century old. The issues raised concerning union violence in “The Right to Work: The Story of the Non-Striking Miners,” which appeared in the January 1903 issue of the legendary muckraking magazine McClure’s, remain very relevant today.

McClure’s editor introduced Ray Stannard Baker’s article by stating that the time had come for concerned Americans to “distinguish between unionism and the sins of unionists,” just as the public already had for some time distinguished “organized capital and the sins of capitalists.” Toward that end, McClure’s assigned Baker to investigate “the conditions under which” roughly 17,000 miners worked in 1902 — the men who refused, for one reason or another, to participate in that year’s coal strike in Eastern Pennsylvania, often referred to as the Anthracite Coal Strike. Baker’s report on what he found may be seen in the first link above.

Writing in an age that was excessively focused on ethnicity and race (of course, our times are hardly perfect in that regard!), Baker paid too much attention to whether the miners and their family members he wrote about were Scottish, English, Irish, Hungarian, Polish, etc. But his depictions of a number of the acts of extortion, vandalism, property destruction, assault and murder perpetrated by union militants against non-striking miners, their family members, and a couple of union card-carrying hunters who found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time, remain vivid and horrifying even a century later. In many cases, Baker allowed the non-striking miners to speak for themselves. This turned out to be a very effective means of countering Big Labor’s efforts, already sadly common at that time, to dehumanize workers who disagreed with union officials.

Baker’s replication of a letter to the editor of the Scranton Tribune by non-striking miner David Dick is a case in point:

MR. DICK’S VERSION OF THE ATTEMPT TO KILL HIM.

EDITOR Scranton Tribune.

SlR: Your paper this morning (Monday) contained an account of the recent attempt on my life, which has several inaccuracies. I therefore send you a correct version, for I think the public ought to know how some persons are treated in this so-called “free country.” On Tuesday evening, September 23, my next-door neighbor, Edward Miller, called at my house and spent some time with us. Shortly after 11 o’clock he left us to go home. I accompanied him to the gate in front of our house. Just as we said “good-night” I turned to reenter the house. Two shots were fired behind me; the shots whistled past my head and lodged in the door in front of me. The night was dark and it was impossible to see any one. My wife is an invalid. Imagine the shock when my family realized that a deliberate attempt had been made on my life. A short time ago, my son, James Dick, had his home attacked at night by an angry mob. The windows were smashed and the house so damaged that he had to move his family out and come to my place for shelter. Now, why these depredations? Because my son and I try to earn a living for our families. I have been in this country thirty years, and have worked all these years as an engineer. I have tried all my life to live peaceably with all men. I am not a member of the union or any other organization, except the Christian church. When the order was given for engineers to quit work, like many others, I did not obey the orders. Why should I? The company had given me a support in return for my work — I considered myself fairly treated; I had no grievance. Further, I disagreed with the policy of destruction and revenge which the proposed flooding of the mines implied. I admired the attitude of Mr. [John] Mitchell [United Mine Workers union president from 1898 to 1908] in the strike two years ago, when he said the property of the companies should be protected, and went so far as to say that men who served as deputies should not be discriminated against when the strike ended. Now, all this is reversed, and I claim my right as a free man to do what my conscience approves. My forefathers died in Scotland for what they believed to be right, and now, once for all, let me say that I propose to work for my home and loved ones. If I am murdered for this, then I ask my enemies to face me in the daylight and not come skulking around a man’s house in the dead of night and fire when my back is turned. No attempt has been made by the civil authorities to find a clue to the perpetrators of these outrages. I cannot but think if I occupied a position on the other side of the labor question what has happened would be heralded far and wide as an illustration of the tyranny of the operators or their friends. I write in the interest of freedom and justice and the rights of workingmen under the Stars and Stripes in this “land of the free and home of the brave.” We have our suspicions of the guilty parties, and if we are correct, they are not far away from us.

DAVID DICK.

Old Forge, September 29, 1902.

In our 21st Century economy, for various reasons, violence appears to be considerably less effective than it once was as a tool for union bosses and their militant followers to obtain what they want. For that reason, primarily, violence is less routine than it was years ago. But Big Labor-instigated threats and assaults against workers who cross the union brass continue in our day. (See, e.g. the second link above.) And in recent decades, unlike in 1902 or 1903, such violence has actually enjoyed a special privileged status under federal law. In the 1973 case U.S. v. Enmons, a divided U.S. Supreme Court went so far as to rule that threats, vandalism and violence perpetrated to obstruct commerce is exempt from federal prosecution – as long as the perpetrators are pursuing “legitimate union objectives.†Writing for the majority, Justice Potter Stewart reasoned that Congress had intended to apply the Hobbs Anti-Extortion Act of 1946 only “to those instances where the obtaining of the property would itself be wrongful because the extortionist has no lawful claim to the property.” Since striking union militants have a legal right to seek a contract they regard as more favorable, Stewart concluded, any violence they resort to towards that end is not extortion.

Fortunately, legislation now before both chambers of Congress would close the loophole opened up in the Hobbs Act by Stewart and his colleagues four decades ago. Enactment of this measure, known as the Freedom from Union Violence Act (S.3178 and H.R.4074), would make it substantially less difficult for law enforcement to bring to justice union officials who incite or orchestrate extortionate violence.